Source & Author: WhoFishesFar.org

On 29 July 2015, Oceana and its partners (See Note) launched the Who Fishes Far database. This pioneering tool in fisheries transparency makes details of EU fishing vessels operating outside Union waters accessible to the public for the first time.

Today, the details of more than 6,800 additional vessels have been added to Who Fishes Far, bringing the database for EU vessels to just over 22,000.

All of these vessels, fishing in every major ocean, operate under the Fishing Authorisation Regulation 1006/2008 (FAR) which governs EU vessels seeking the right to fish externally. This law is in the process of being reformed to bring it into line with other EU legislation promoting transparent and sustainable world fisheries (more on this below).

The data makes very clear the enormous scale and reach of the EU’s external fleet. In addition, the significance of the availability of this information cannot be overestimated. It has only been made public via access to information requests to the European Commission, and is a much needed boost to the transparency of the European fleet, permitting the assessment of vital fishing authorisation data by researchers, national or local fisheries authorities and NGOs, and facilitating much needed public accessibility.

New data developments

Who Fishes Far now supports data for all fishing authorisations in existence since the FAR was created in 2008, including foreign vessels fishing in EU waters. It shows that:

- Certain fleets such as those of Belgium, Denmark, Estonia and Sweden, tend to operate close to European waters in the North East Atlantic

- France, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain and UK were authorised to fish off the coasts of West-Central Africa (Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Morocco, São Tomé and Príncipe and Senegal)

- French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and UK vessels operate in the Indian Ocean (in IOTC area, and under official EU access agreements with Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique and Seychelles).

- German, Polish and Spanish vessels were authorised to fish in Antarctic waters (in CCAMLR area)

- In the South Pacific vessels from the Netherlands, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal and Spain were authorised to fish (in SPRFMO area)

- European flagged vessels operating in the Western Pacific are all fish carriers (in WCPFC area)

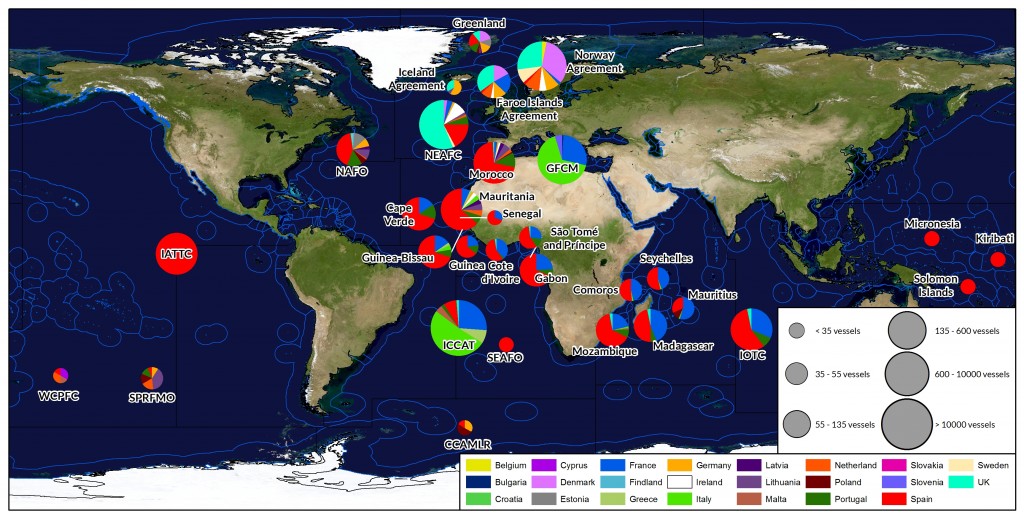

Map showing where EU vessels have been authorised to fish under the Fishing Authorisation Regulation between 2008 and 2015. In total, over 22,000 individual EU vessels received FAR authorisations during this period. (Excludes private agreements)

Abbreviations: SEAFO – South East Atlantic Fisheries Organisation; WCPFC – Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission; CCAMLR – Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources; SPRFMO – South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation; NAFO – Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organisation; IATTC – Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission; IOTC – Indian Ocean Tuna Commission; GFCM – General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean; NEAFC – North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission; ICCAT – International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas.

Abbreviations: SEAFO – South East Atlantic Fisheries Organisation; WCPFC – Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission; CCAMLR – Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources; SPRFMO – South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation; NAFO – Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organisation; IATTC – Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission; IOTC – Indian Ocean Tuna Commission; GFCM – General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean; NEAFC – North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission; ICCAT – International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas.

Notes to map:

The map shows vessels fishing under the following three different types of fishing agreement/authorisation:

- Bilateral Agreements: the circles labelled with individual country names are those for which official EU access agreements or (Sustainable) Fisheries Partnership Agreements are currently in place, or were previously in place during the period 2008-2015.

- Reciprocal Agreements: the circles labelled Iceland Agreement, Norway Agreement and Faroe Island Agreement refer to agreements covering the joint management of shared stocks between the EU and Iceland, Norway and the Faroe Islands. Under FAR authorisations, EU vessels can fish in Norwegian, Icelandic and Faroese waters, and vice versa.

- Authorisations for EU vessels to operate within a Regional Fisheries Management Organisation (RFMO) Convention Area. RFMOs are international organizations formed by countries with fishing interests in an area of the ocean.

Each circle indicates the number of individual EU vessels authorised to fish under the relevant Bilateral or Reciprocal Agreement, or within the specified RFMO Convention Area, during the period 2008-2015. To note that a single vessel may have received multiple authorisations to fish under multiple agreements during this period (e.g. in the waters of different non-EU countries).

See graphs below for more detailed information

Data gaps persist

Despite the importance of the Who Fishes Far data, it is actually what is NOT included that tells the most important story about problems with the control system for the EU’s external fleet. Of particular concern are two data voids.

The first is that the database only includes vessels which fish externally under public access agreements, for example where the EU pays countries to allow its vessels to harvest surplus stock (Sustainable Fisheries Partnership Agreements or SFPAs).

There is no data on EU vessels fishing under private agreements and chartering arrangements[i]. This is where an EU operator contracts directly with a non-EU country or company to fish.

Under the current system, there is no centralised system to gather information on these private agreements, a significant loophole which means a large portion of the EU’s external fishing activity is not subject to any level of scrutiny. Coupled with other weaknesses in the system, it means these vessels are able to operate outside the scope of EU law and standards.

The second void in the data concerns the lack of globally used unique vessel numbers. Who Fishes Far only includes the EU vessel identifier – the Community Fleet Register Number or CFR – that is used exclusively for EU vessels. A global system of vessel numbering has been set up by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO). This number stays with the vessel throughout its life, and is not changed or deleted upon changes of ownership. This system provides a centralised, consistent and accessible method for identifying vessels and tracking their history and cost nothing to obtain. IMO numbers are currently not mandatory for fishing vessels seeking FAR authorisation, hence their absence from the database[ii].

Reforming the FAR: accountability of the EU Fleet

The missing data in Who Fishes Far tells us much about the inherent weaknesses in the current Regulation that permit certain vessels to evade the compliance and disclosure requirements, and underlines the need for robust reform.

Core problems with current system:

Private or chartering agreements are typically negotiated, concluded and conducted under almost total opacity, outside the legal frameworks of the EU ‘s public access agreements which impose strict standards on operators in terms of labour laws and fishing sustainably. A robust system must ensure ALL vessels, regardless of where and under which type of agreement they wish to fish, must be subject to the same strict standards.

Abusive re-flagging by EU vessels and lack of IMO number on application: under the current FAR, EU vessels which have been operating under flags of countries known to be failing in their efforts to stop illegal fishing have been able to return to the EU fleet and obtain a fishing authorisation with relative ease, without proper crosschecks of the legality or sustainability of their activities under non-EU country flags.

Because vessels currently do not need to have an IMO number before applying for an authorisation, little information is available to Member States about the activities of the vessel when it was fishing under a non-EU flag. In addition, EU vessels do not have to provide any information on their activities under non-EU flags in their application for an authorisation to operate in non-EU waters. In the future system, any vessel leaving and coming back to an EU flag should be required to prove that the activities of the vessel have been compliant with EU and international conservation and management measures and laws. In addition, any fishing vessels applying for a fishing authorisation should have an IMO number.

Current system dents the EU’s reputation in the fight against IUU Fishing

It is particularly concerning that the stated weaknesses in the current FAR may have the potential to undermine the leading role of the EU in the global fight against illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. There are few doubts that the EU’s carding system under EU’s strict IUU Regulation[iii] is having a positive impact and raising the bar in respect of third country compliance with IUU fishing control standards. However, as gatekeeper of the legal integrity of seafood supply to its global seafood market, the EU has a moral duty to demonstrate the due diligence standards that it seeks to promote.

Revision of the FAR regulation – an opportunity for change

The Commission’s proposal for a new regulation on the sustainable management of external fishing fleets (EC 2015/0636) was published in December 2015.

If adopted in full, it will tighten requirements for fishing under private and chartering agreements, stop unjustified reflagging activity, and mandate IMO numbers for external fishing.

Finally, and this returns us to the Who Fishes Far website, the new system would ensure that basic details (such as vessel name and flag for all types of agreements – including private and chartering) on all vessels authorised to fish outside the EU are included in a proposed electronic register, accessible via an official public platform for the first time. This would be a global transparency landmark, and mean Who Fishes Far has achieved its goal – to make itself redundant.

A number of States have raised objections to elements of the proposal, and a crucial European Council session in late June will determine the way forward. It is essential that the reforms are carried through, not only to achieve and maintain fisheries sustainability, but also to ensure the continued leadership of the EU in matters of global fisheries governance.

[i] EU companies undertake private agreements with certain non-EU countries that grant them private access to fish resources in the waters of these coastal states. This is only allowed in the waters of third countries where there are no SFPAs in place. In addition, EU companies make chartering agreements for their EU vessels to access the resources of certain coastal states in collaboration with local companies.

[ii] From 1 January 2016 onwards, IMO numbers have been made mandatory for all vessels above 24 meters in length fishing in EU waters and EU vessels over 15 meters fishing in non-EU waters . However, to fish in non-EU waters all activity should be monitored, regardless of the size of the vessel. Therefore, any fishing vessels applying for a fishing authorisation should have an IMO number in order to increase transparency and allow the effective tracking of the vessel’s behaviour. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/1962 of 28 October 2015 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 404/2011 laying down detailed rules for the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 1224/2009 establishing a Community control system for ensuring compliance with the rules of the common fisheries policy

[iii] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2015:480:FIN

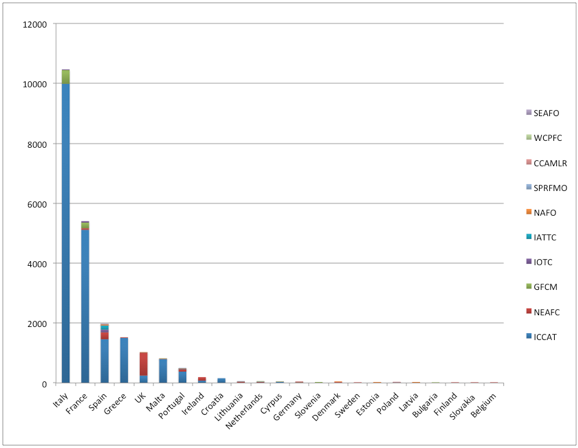

Figure 1: Numbers of vessels flagged to EU member states fishing in areas managed by Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) during the period 2008-2015

Abbreviations: SEAFO – South East Atlantic Fisheries Organisation; WCPFC – Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission; CCAMLR – Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources; SPRFMO – South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation; NAFO – Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organisation; IATTC – Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission; IOTC – Indian Ocean Tuna Commission; GFCM – General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean; NEAFC – North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission; ICCAT – International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas.

Figure 1 shows the number of vessels flagged to EU member states fishing in areas managed by Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) for the period 2008-2015. RFMOs are international organisations formed by countries with fishing interests in an area of the ocean. Individual vessels may be counted more than once in the above graph, as a vessel can have authorisations for multiple RFMOs. In addition, a vessel could have changed its flag to another member state.

During the period 2008-2015, nearly 20,000 EU vessels were registered to fish within the ICCAT Convention Area (that is, the area of ocean managed by a particular RFMO) for the whole or part of this period. Almost half of these vessels were flagged to Italy, which has authorised large numbers of vessels to operate in the ICCAT area to target swordfish. The graph highlights key differences in the fishing activities of different member states, with some member states staying relatively close to home (e.g. the majority of UK vessels fishing in the northeast Atlantic under NEAFC) and others fishing much further afield in areas of, for example:

- the Southern Ocean, e.g. German, Polish and Spanish-flagged vessels fishing in the CCAMLR Convention Area;

- the Indian Ocean, e.g. French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and UK-flagged vessels fishing in the IOTC Convention Area;

- the South Pacific Ocean, vessels from the Netherlands, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal and Spain were authorised to fish in the SPRFMO Convention Area

- The Western Pacific Ocean, fish carriers were authorised to operate from Cyprus, Malta, the Netherlands and Spain (in WCPFC area)

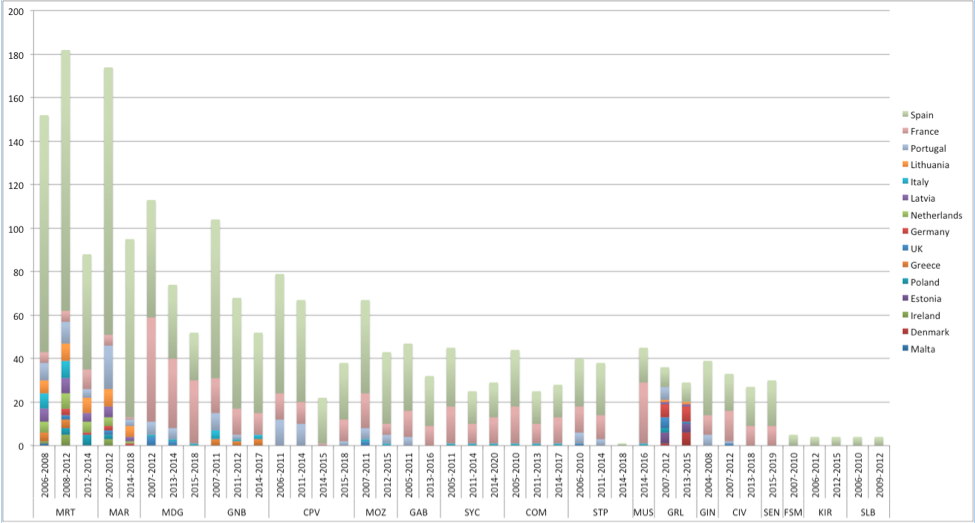

Figure 2: Numbers of vessels flagged to EU member states authorised to fish under official EU access agreements or (Sustainable) Fisheries Partnership Agreements during the period 2008-2015

Abbreviations: MRT – Mauritania; MAR – Morocco; MDG – Madagascar; GNB – Guinea-Bissau; CPV – Cape Verde; MOZ – Mozambique; GAB – Gabon; SYC – Seychelles; COM – Comoros; STP – São Tomé and Príncipe; MUS – Mauritius; GRL – Greenland; GIN – Guinea; CIV – Côte d’Ivoire; SEN – Senegal; FSM – Federated States of Micronesia; KIR – Kiribati; SLB – Solomon Islands

Figure 2 shows the number of vessels flagged to EU member states authorised to fish under official EU access agreements or (Sustainable) Fisheries Partnership Agreements (together termed “bilateral agreements”) during the period 2008 to 2015. The years along the horizontal axis refer to the duration of the bilateral agreement concluded between the EU and the non-EU country – for most non-EU countries in the graph above (with the exception of Mauritius, Guinea, Senegal and Federated States of Micronesia) more than one bilateral agreement corresponds to the 8-year period of study. Individual vessels may be counted more than once in the above graph where they have been authorised to fish under more than one agreement for a particular non-EU country (e.g. in successive years) or under agreements for more than one non-EU country.

During the period 2008-2015, EU vessel activity was highest in West and Central Africa and the Western Indian Ocean. In order of importance, in terms of numbers of EU vessels fishing in their waters, were the following countries (numbers of individual vessels in brackets):

- West Africa: Mauritania (214), Morocco (199), Guinea-Bissau (116), Cape Verde (90), Guinea (39), Cote d’Ivoire (37), Senegal (30)

- Central Africa: Gabon (58), São Tomé and Príncipe (52)

- Western Indian Ocean: Madagascar (124), Mozambique (74), Seychelles (54), Comoros (52), Mauritius (51)

Spain had the highest number of vessels fishing under bilateral agreements during this period, followed by France, Italy, Lithuania and Portugal.

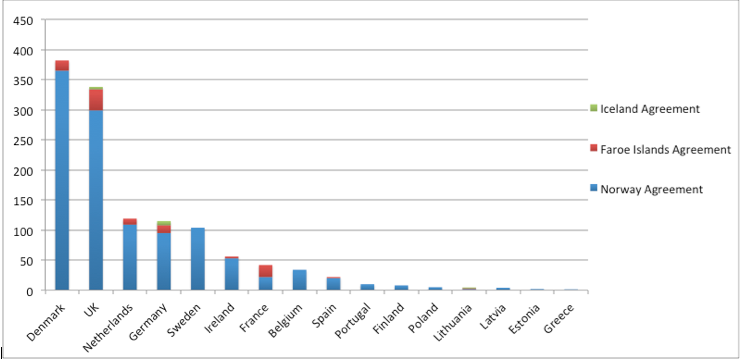

Figure 3: Numbers of vessels flagged to EU member states authorised to fish under Reciprocal Agreements with Iceland, Norway and Faroe Islands during the period 2008-2015

Figure 3 shows the number of vessels flagged to EU member states authorised to fish under Reciprocal Agreements for all or part of the period 2008-2015. Reciprocal Agreements refer to agreements covering the joint management of shared stocks between the EU and Iceland, Norway and the Faroe Islands, respectively. Under FAR authorisations, EU vessels can fish in Norwegian, Icelandic and Faroese waters, and vice versa. (Note that individual vessels may be counted twice in the above graph where they fished under more than one Reciprocal Agreement, or under the flag of more than one EU member state, during the 8-year period.)

Note: Oceana is working in a coalition of non-governmental organisations to secure the harmonised and effective implementation of the European Union Regulation to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. The revision of the EU’s external fishing fleet regulation is essential to ensure that all fishing activities by EU nationals or entities, wherever they occur, are transparent, accountable and sustainable, in line with the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) and the EU’s policies to combat illegal fishing globally.

For more information see: www.whofishesfar.org or http://www.iuuwatch.eu/iuu-fishing/far/

[i] EU companies undertake private agreements with certain non-EU countries that grant them private access to fish resources in the waters of these coastal states. This is only allowed in the waters of third countries where there are no SFPAs in place. In addition, EU companies make chartering agreements for their EU vessels to access the resources of certain coastal states in collaboration with local companies.

[ii] From 1 January 2016 onwards, IMO numbers have been made mandatory for all vessels above 24 meters in length fishing in EU waters and EU vessels over 15 meters fishing in non-EU waters . However, to fish in non-EU waters all activity should be monitored, regardless of the size of the vessel. Therefore, any fishing vessels applying for a fishing authorisation should have an IMO number in order to increase transparency and allow the effective tracking of the vessel’s behaviour. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/1962 of 28 October 2015 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 404/2011 laying down detailed rules for the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 1224/2009 establishing a Community control system for ensuring compliance with the rules of the common fisheries policy

[iii] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2015:480:FIN